On November 23, 2024, Deportivo Cuenca played its final home game of the year. It was a calm Saturday in Cuenca, but something unexpected happened during halftime. A flash of lightning and the sound of thunder echoed through the stadium stands. Strangely enough, the crowd's immediate reaction was one of joy. Spectators cheered with excitement as if a goal had been scored and applauded with smiles on their faces. It is even rumored that a few tears ran down the cheeks of some Cuencanos.

This was a reflection of the emotional state and the new significance of rain in a city that, just days before, had organized a procession with the “Señor de las Aguas” (Lord of the Waters) to pray for an end to the drought. Since July of this year, Ecuador has been going through one of its darkest moments—literally. The country has experienced power outages lasting up to 14 hours a day. The regional drought affected Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, but its impacts were felt especially in Ecuador due to its vulnerability and lack of planning. Moreover, it can be assumed that the effects on the rivers have worsened due to the preceding drought at the end of 2023. In this context, a common question among Ecuadorians was: “When will it rain in Cuenca’s rivers?” This area is of national interest because it feeds the Paute River, which powers Ecuador’s main hydroelectric complex: Paute Integral.

Motivated by this need, our SWACH team began investigating if we could contribute. Even though, our expertise and focus are centered on climate change and climate projections, we could not ignore the reality of the crisis and decided to search for a weather forecasting alternative that would be accessible and easy to interpret for decision-makers. While browsing online, we came across the World Climate Service portal. In one of their blog posts, they discussed the relationship between the Tropical North Atlantic Index and drought in the Amazon. Additionally, their website highlighted their scientific credentials and offered a free trial to explore the platform. Their slogan caught our attention: “If you knew then what we knew then.” We wanted to know what they knew!

We reached out via email and received a response from Jan Dutton, PhD, CEO of Prescient Weather Ltd. After explaining the dramatic situation our country was facing, they generously offered us free access to their forecasting system for several months. We then had a virtual meeting demonstrating the use of the tool and agreed to use it to support national-level decision-making. Although, we as researchers are not directly responsible for those processes, we are in contact with various regional institutions and wanted to contribute in any way with our grain of sand.

In short, World Climate Service offers two types of forecasts: seasonal and sub-seasonal. The former focuses on climate conditions for the next 1 to 6 months. It is important to note that these are not weather forecasts, but rather predictions of climate conditions being average, above, or below average. The latter—sub-seasonal forecasts—provide weather and climate predictions for the next six weeks. Due to the country’s urgent needs, these sub-seasonal forecasts were the ones we explored most.

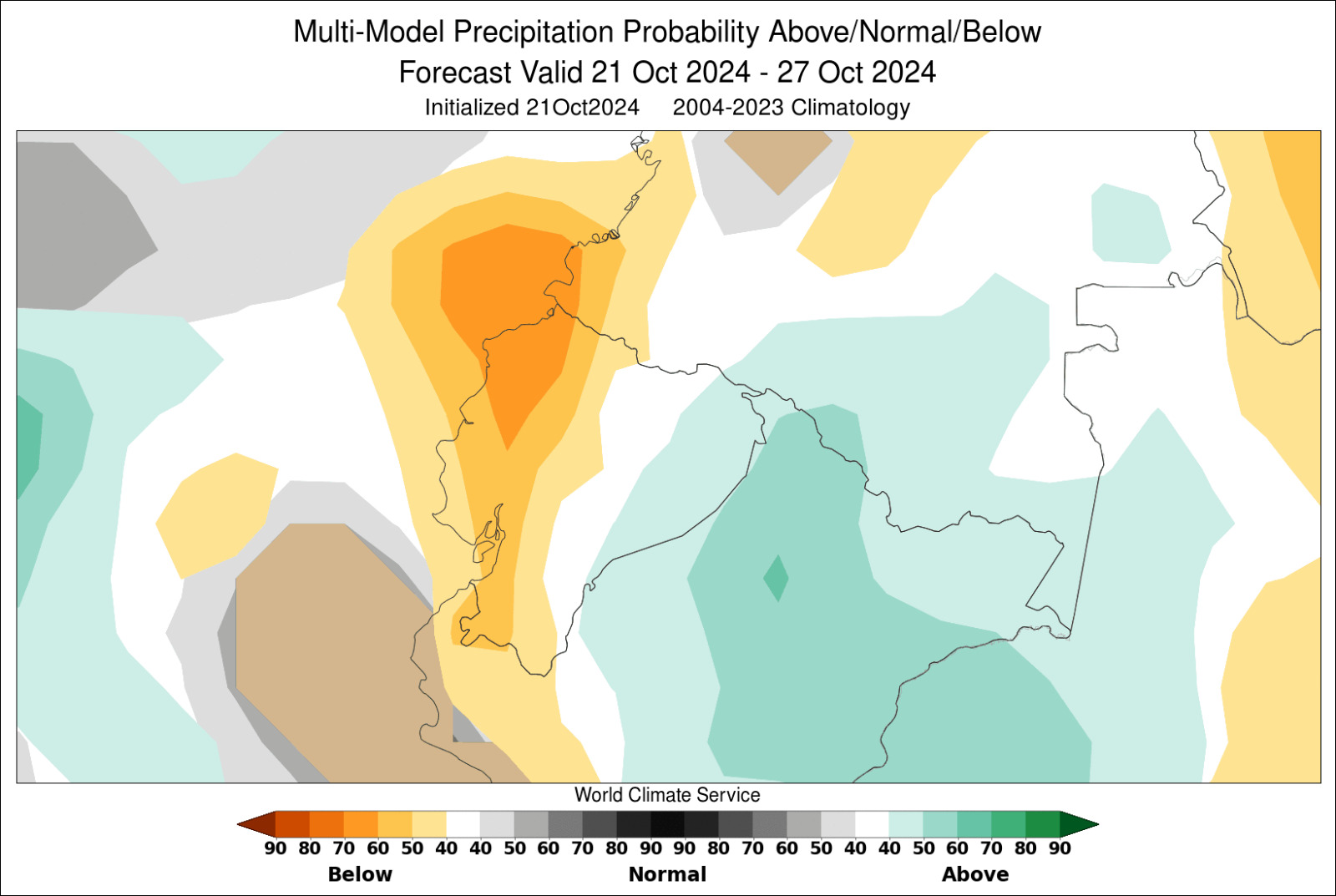

Informally, we have shared these forecasts with representatives from various national institutions. We even circulated the forecast images among hydrology professionals to promote their use. Although there are currently many alternative portals and seasonal forecasts, we noticed a strong interest in products that are easy to access and interpret and that bring together multiple sources of information in one place. Anecdotally, we were able to verify the spatial accuracy of the forecasts during the week of October 21–27. That week heavy rainfall occurred in the cantons of Paute and Guachapala (east of Cuenca), but no rain fell in the highlands of Cajas, which supply Cuenca’s drinking water. Days earlier, we had shared the forecast with officials and analyzed that the drought would not be as widespread in the southern region, but rather would be concentrated in the upper Paute basin (west), while normal conditions were expected in the lower basin (east). Although this may have seemed like good news for citizens, in reality, it complicated the water supply situation.

Figure 1. Weekly forecast of abnormal precipitation probabilities based on the multi-model ensemble.

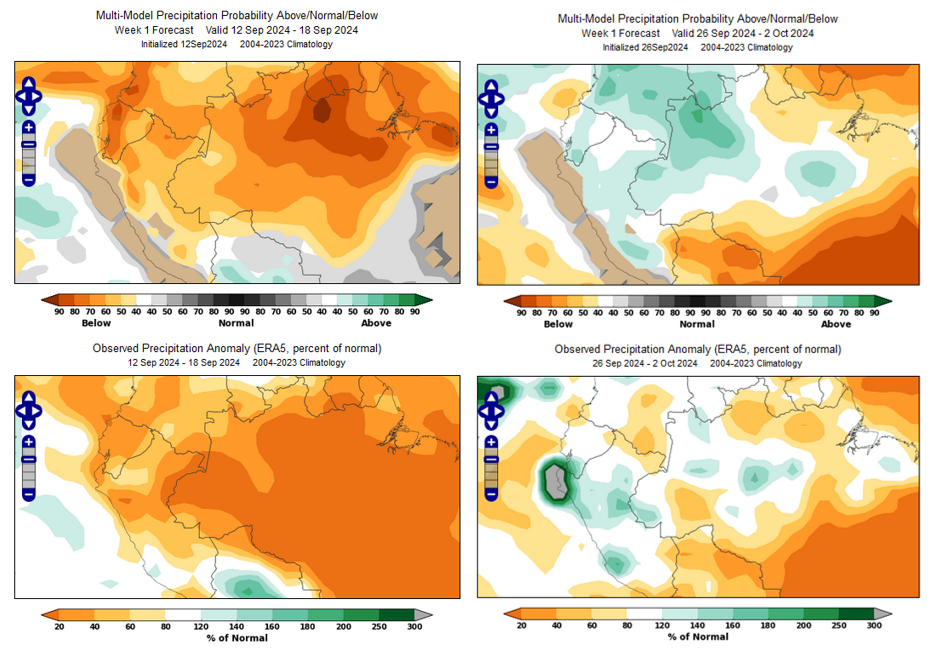

Continuing with the review, the portal includes a quantitative verification tool that compares forecasts with observed data using ERA5 reanalysis data. While we are aware that the spatial resolution and accuracy of this product in the Andean region are limiting factors, it nonetheless allows for an estimation of its performance. Future research could incorporate local data to better assess the accuracy of the forecasts. For now, we present in the images two weeks of forecast verification. Both negative and positive precipitation anomalies were accurately predicted in the southern region.

Figure 2. Verification between Weekly Forecasts with Negative (Left) and Positive (Right) Precipitation Anomalies

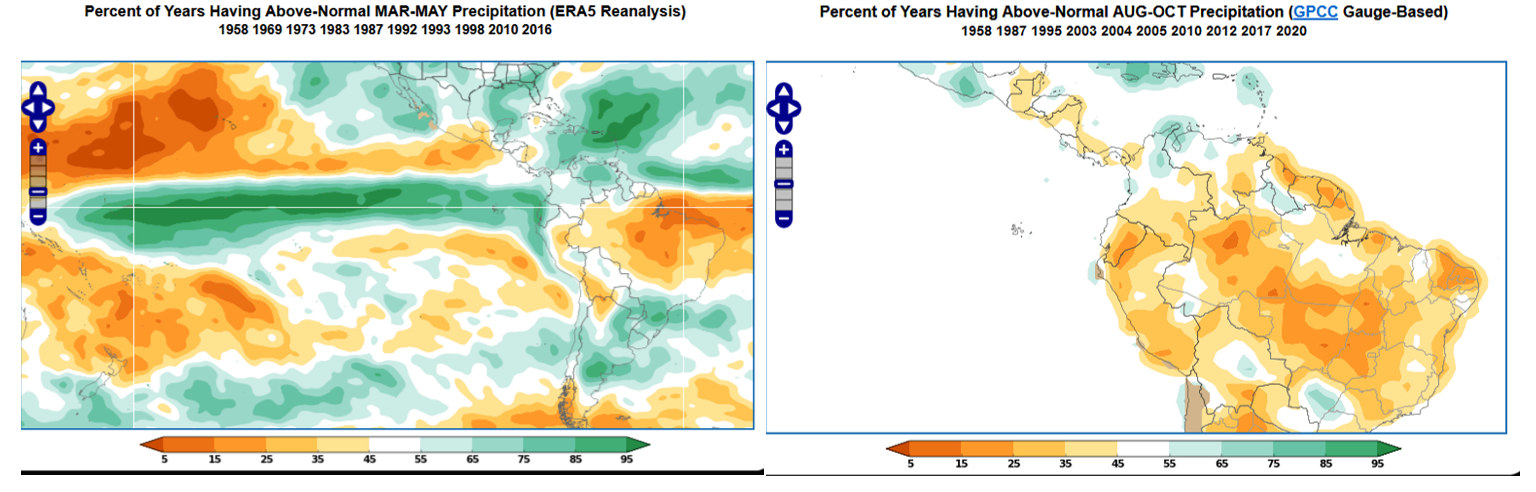

In addition to climate forecasts, the WCS (World Climate Service) portal provides access to forecasts of climate indices, tools for assessing model skill and performance, and a particularly promising feature for climate condition analysis known as the Climate Index Analogues. This tool allows users to filter historical years that exhibited specific climate conditions during selected months and view the percentage of those years that experienced anomalies in temperature, precipitation, wind, or radiation.

For instance, users can filter what years have had had a strongly positive ENSO index and examine the expected global anomalies associated with those conditions. It is a known fact that the years hit by El Niño phenomenon are typically associated with heavy rainfall along Ecuador’s coast.

Figure 3. Percentage of the years with Precipitation Anomalies during a Strong El Niño Event (Left) and a Very High TNA (Right)

Likewise, we identified a pattern that is not widely studied or recognized but appears to be related to the 2024 drought. When filtering for years with a strongly positive Tropical North Atlantic (TNA) index between June and October, we observed that precipitation tends to be below normal in the Ecuadorian Amazon between August and October. This is precisely what occurred in 2024.

Throughout this period, we have made efforts to share this tool with institutions in Cuenca and Quito. We are aware that efforts are being coordinated to enable institutions to access these services in real time and on a continuous basis. Regardless of the agreement modality between providers and institutions, at SWACH we reaffirm the importance of integrating climate services into decision-making processes. It is essential to incorporate scientific evidence, numerical data, probabilities, and uncertainties into short-, medium-, and long-term water resource planning in order to support national development and avoid repeating such a dark chapter in our history.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Bohon, C. (2024) Índice del Atlántico Tropical Norte. Impactos inmediatos // Tropical North Atlantic (TNA) Index: Immediate Impacts. Blog de World Climate Service. Disponible en: https://www.worldclimateservice.com/2024/09/11/tropical-north-atlantic-index/

- Pérez, B. (2024, 20 de noviembre). El «Señor de las Aguas» trajo lluvia a Cuenca. Diario El Mercurio. Disponible en: https://elmercurio.com.ec/2024/11/20/el-senor-de-las-aguas-trajo-lluvia-a-cuenca/

- Diario El Comercio. (2024, 22 de octubre). Cuenca registró lluvias la tarde de este martes 22 de octubre ¿Cuál es la situación de sus ríos? Disponible en: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/ecuador/cuenca-lluvias-rios.html

- Portal World Climate Service disponible en: https://www.worldclimateservice.com/

Santiago Núñez Mejía

Doctoral Researcher, SWACH Project.